Enterprise babelfish?

For those who have not read or heard of the babelfish – you can find it in Douglas Adam’s “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”. Placed in your ear, the babelfish provides instant translation of any language being spoken by any alien you might encounter.

In thinking of my role as enterprise architect, business architect, business analyst, business synthesist in the many different enterprises with whom I have engaged, I realised that one of the important capabilities that I bring to bear is the capacity to understand an enterprise and the various ways in which each organisation or organisational entity thinks and communicates about themselves.

This article explores the need, nature and value of the role of enterprise babelfish and offers a different way of thinking about the role that various enterprise change professionals fulfill within the enterprises with whom they engage.

Business context and need

In any enterprise, there are special words and expressions that form part of the way in which the enterprise speaks of itself, encompassing:

- vision and mission

- culture and values

- products and services

- value propositions and differentiators

- processes and ways of doing things

Understanding the intended meanings of these words and expressions is an important element in being part of the organisation and contributing to its operation, development, management and governance.

The larger the organisation, the more likely it is, that there are differences in understanding and articulation which result in different attitudes and behaviours, with the potential to limit the development and performance of the organisation.

Two influencing factors relate to how we use language and how we use models in our thinking and communication. In these respects, it is helpful to appreciate aspects of:

- denotation and connotation

- perception and conception

The first of these was drawn to my attention by Len Fehskens. The latter is more of a hypothesis of my own!

Denotation and connotation

For many words, but particularly for those words and expressions that reflect the essence of the identity and operation of an enterprise, there are two facets to their meaning:

- the particular meaning that is denoted by the word or expression

- the related concepts and expressions that are connoted by the word or expression

A simple example – wheel:

- denotes a circular object fixed to another to enable movement

- connotes an ability to rotate and having an axle

It is important that the appropriate denotation and connotations are formed – otherwise, a different meaning or interpretation may be made by others.

I have encountered numerous situations where different people in an enterprise use the same word or expression, but where the connotations associated with the expression they are using are quite different – to the point that the difference prompts use of completely different business processes. In one client setting, the term “Work Pack” meant a Work Order in one Division and a Scheduled Operation (part of a Work Order) in another Division. This difference was sufficient to mean that common systems, processes and practices were not feasible across Divisions until consistent definitions and processes were established.

As enterprises give attention to consistency in denotation and connotation of key terms and language, they are developing greater self-awareness and greater capacity to effect change and operate in a more integrated and consistent manner across the enterprise.

Perception and conception

As we encounter and interact with the enterprises of which we are part, we build mental models of the enterprise, based on our perception of how the enterprise operates. Inevitably, we have very limited exposure to the full operation of the enterprise, so our perceptions lead to widely varying mental models of the enterprise. This is reflected well in the story of the blind men who encounter an elephant, each describing what they have encountered based on the limited point of contact that they have.

Our perception is influenced, not only by the limited parts of the enterprise to which we have exposure, but also by the nature of the interactions we have – by what we observe about the thinking, attitude and behaviour of leaders, managers, peers and others.

Another element to our understanding of any enterprise relates to our conception of the enterprise – the model that we build of the entire enterprise, based on inputs such as:

- corporate documents espousing vision, mission, purpose, objectives and strategies

- organisational structure, policies and other elements describing how the enterprise is organised

- similar materials available for each of the organisational units of which the enterprise is comprised

This enables us to develop a “high level” model or “conceptual” representation of the enterprise. Not surprisingly, there can be significant gaps between our conception and our perception of the enterprise.

Barriers to understanding

There are a number of barriers to shared understanding, including how we deal with and think of our enterprises.

Systems

Organisations and enterprises can be conceived as systems-of-systems. This, in its own right, leads to numerous views of interwoven systems. One only needs to consider a generic, high level operating model (see related article – Operating models) to appreciate how many systems might exist in any enterprise.

The vast majority of organisations entail human activity in combination with supporting technology, introducing considerations in relation to:

- Human activity systems (HAS)

- Information systems used by these HAS

- IT systems and other technology based systems also used by these HAS

with a long history of difficulties in designing and implementing an effective combination of HAS / IS / ITS / TBS which effectively enhance enterprise performance.

Add to this that systems can be conceived of through conceptual models, designed through logical models and implemented in accord with physical models, and we have further added dimensions of complexity.

Beyond these factors, there are others which become evident as one explores the disciplines encompassed within the broad realm of “systems thinking”.

Models

There are various types of models at play within enterprises, including but not limited to:

- Each of us have mental models of the world and the enterprise with which we engage and interact

- Our information systems (whether paper based or digital) are a model of how the enterprise sees the environment in which it operates, its interactions with this environment, and its internal activities.

- Our planning, designing and managing activities often develop models as a means of communicating intentions or exploring options

Our engagement in the development and operation of our enterprises requires us to better understand these different types of models, and to deal with the range of inherent conflicts which inevitably arise between the various models we use, whether individual or shared models.

Complexity

As we start to explore organisations and the enterprises they pursue, it does not take long to realise that, like human beings, organisations are complex entities. This leads to a number of different issues as no individual can hold within their mind all elements that go to make up the structure and behaviour of an organisation. The implications of this include:

- Each individual may have a different perception and conception of the organisation

- A complete conception of the organisation requires multiple individuals to create and sustain

- Common models and a common language and narrative will be required to deal with these implications

Role of enterprise babelfish

And so it is, that I see an invaluable role for those within an enterprise that have the capability of the babelfish to:

- recognise the different languages and models being used within our enterprises

- enable the enterprise to develop a more consistent expression of its aspirations, intentions and mode of operation

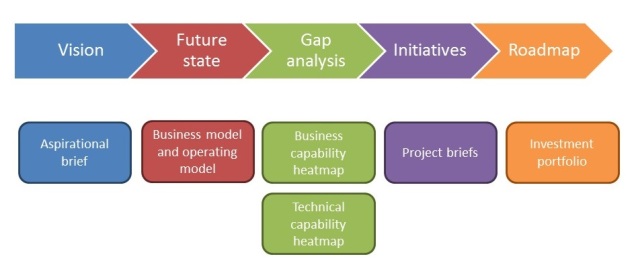

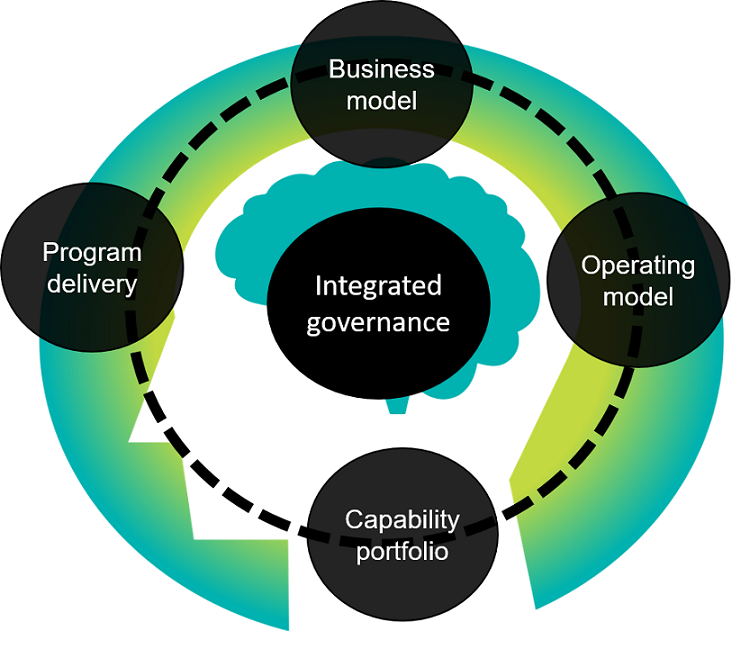

- facilitate processes whereby business transformation can be more effectively planned and executed

In so doing, those fulfilling this role will contribute to developing greater self-awareness as an enterprise, to more effective development, and hence to enhanced performance, viability and sustainability of the enterprises of which they are part.

Over the last two and a half years, I have written and published over 50 articles which relate to architecting and transforming enterprises. These have been published on LinkedIn and an index of all articles maintained in the article “

Over the last two and a half years, I have written and published over 50 articles which relate to architecting and transforming enterprises. These have been published on LinkedIn and an index of all articles maintained in the article “