When I hear expressions such as digital transformation and digital leadership, the following images come to mind:

- Millions of 0’s and 1’s transforming into 2’s and 3’s

- An endless line of o’s and 1’s following each other like lemmings

More seriously, the following questions come to mind:

- What is digital transformation?

- What does it mean to my enterprise?

- What decisions will it require?

Understanding digital transformation

So … let’s unpack digital transformation using some simple equations.

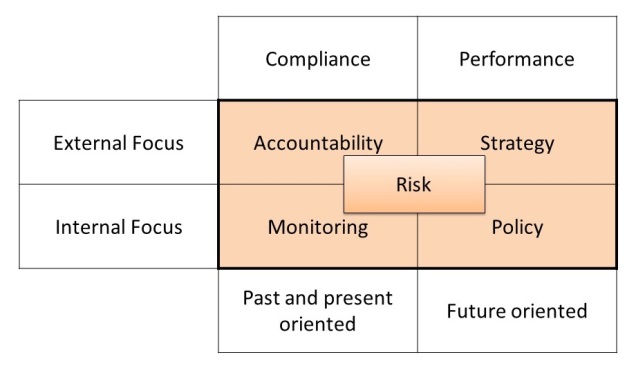

- Digital transformation = digital strategy + business transformation

- Digital strategy = digital products / services + business strategy

Combining the two equations, we get …

- Digital transformation = digital products / services + business strategy + business transformation

For me, that makes things much simpler because:

- I understand what is entailed in business transformation

- I understand what is entailed in business strategy

- Now, I need to understand the implications of digital products and services

Digital products and services

There are several different elements to consideration of digital products and services, including:

- those existing products and services which are amenable to being delivered as a digital product or service

- those new digital products or services which complement existing products and services in such a manner as to enhance the value proposition for existing or new customer segments

- those digital products or services which can be integrated with other digital products and services from within your enteprise or from other sources

Each of these areas offer the opportunity to extend greater value to existing and new customers.

Examples

That all sounds fine – but what does it mean in practical terms for your or my enterprise? And let’s consider some pragmatic examples and not just trot out the usual, unreachable examples such as Amazon, Netflix, Air BnB or Uber!!

Depending on your enterprise – it may prove a valuable exercise, simply to list your products and services. For some enterprises, it is obvious. For others, not quite so easy.

In my own line of business, I provide consulting services. Often, these services are summarised in a deliverable (product). The consulting is largely done face-to-face and on a client site. The deliverable is typically a presentation or a document, already provided in digital form. There will often be several steps in developing the report. The early stages of the consultancy may involve some form of assessment. This could potentially be undertaken via a digital channel, enabling my client to undertake the assessment at a time and in a place that suits them, without needing to coordinate our schedules and our locations.

Of course, this is not feasible for all businesses. A friend who operates a lawn mowing and gardening business is not going to be able to offer an alternative digital product! But that does not mean that there are no digital product / service opportunities. Perhaps there are complementary digital products and services that he might offer? These could relate to:

- booking and paying for his services

- hints and tips for “after-care” of lawns and gardens

Ultimately, the test for complementary digital products and services relates to customer need and potential for the customer to value these, in combination with the physical products and services. A helpful approach to identification and consideration of such opportunities is to consider the “customer lifecycle”, from genesis to lapsing of a particular need. An important consideration in developing and delivering digital services is to consider the customer journey and customer experience. A disjointed, difficult customer experience will not be conducive to business growth in this area.

An example which has been given consideration by governments is the process involved in establishing a new cafe or restaurant. Depending on circumstances, the entire process can require interaction with a number of different government entities (at differing levels of government in differing national contexts) including:

- Registering a business and business name

- Securing licences for selling and serving alcohol

- Gaining local authority approval for food preparation

- Dealing with any entertainment licensing fees

- Subsequent renewal of approvals

Such processes can involve provision of similar information on numerous occasions, and may entail presentation of considerable supporting documentation, through slow and cumbersome office / counter channels. A digital service would allow the prospective business owner to provide the necessary information once and to be able to undertake the process at a time and place of their convenience. This first emerged under a program entitled “Ask just once” – promoting the line of thinking that government agencies would move to a position where they did not repeatedly ask citizens or businesses for the same information.

Another example revolves around considering all the related events which occur in a “life event” such as moving house, where a range of changes occur in relation to:

- the property transactions (sale and purchase)

- utility connections (power, water, telecoms)

- advice of change of address to other organisations

In this scenario, all three elements can prevail – replacing physical services with digital services, offering complementary digital services and integrating a range of digital services to offer greater value and convenience to customers.

Tools and techniques

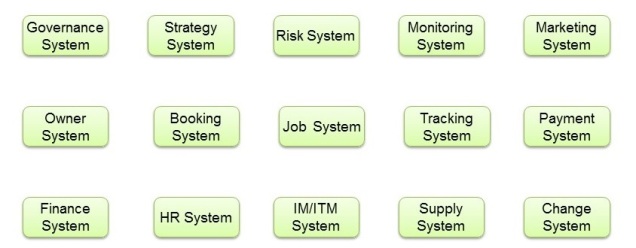

What tools and techniques can be used to identify and explore opportunities and implications as part of developing a suitable digital strategy?

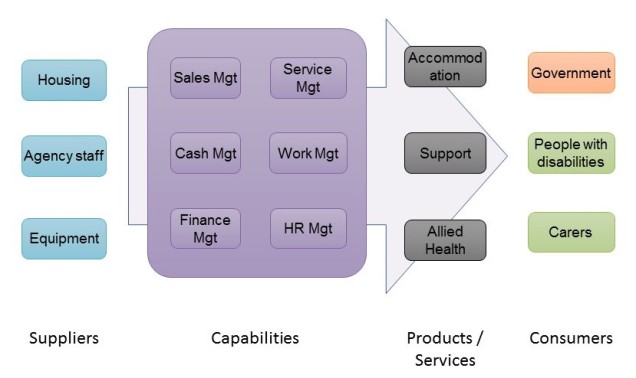

Changing the product or service portfolio can be effectively explored through the discipline of reviewing your enterprise business model(s). Such a review gives cause to considering the viability and sustainability of product and service offerings and their value proposition to customers and consumers.

Better understanding the value proposition for customers should prompt consideration of digital products and services and the use of digital channels to complement existing market channels.

The same disciplines, applied to your enterprise operating model, will enable identification of opportunities for efficiencies and more responsive processes in producing and delivering your products and services, offering greater value to existing or new customers.

Conclusion

Digital transformation calls for thinking about digital products and services which may complement or extend your existing products and services and which will deliver greater value to customers and enable you to offer your products and services to broader markets.

Provision of these digital products and services will leverage existing capabilities within your enterprise, but also require you to strengthen and extend your business and digital capabilities. It will demand that you better understand and manage the inter-dependencies between your enterprise capabilities and their integration to ensure that a seamless and positive customer experience is provided for the new products and services you offer through wider and more convenient channels.

Attention to development of your enterprise in this direction may be critical due to the emergence of digital products and services from existing or new competitors, but also offers your enterprise the opportunity to enter new markets which you have previously been unable to access.