… between people, between systems, between people and systems …

Background

When asked about my work and what I do, I sometimes answer …

I work at the interface between business people and IT people because business people don’t understand IT people, and IT people don’t understand business people

I usually follow that with the quip “and I don’t expect to be out of a job in my lifetime!”

Now, I am one of the leaders of Interface Associates where we seek to cultivate the capability within organisations to more effectively manage a range of interfaces without having a reliance on organisations and people like Interface and our Associates.

Interfaces

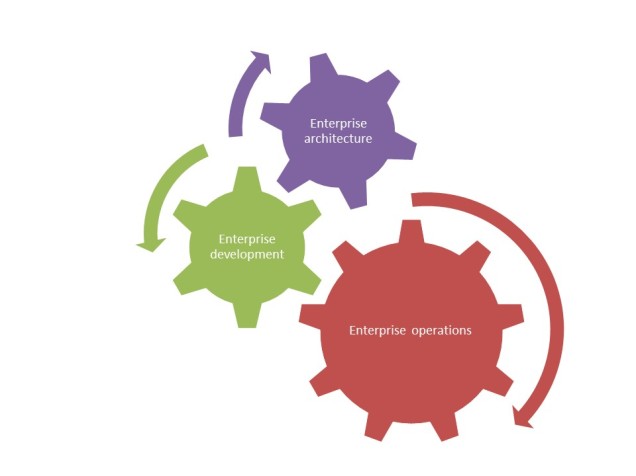

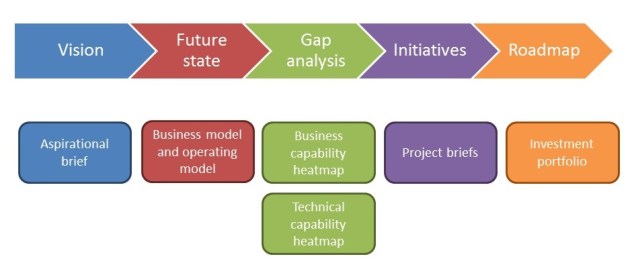

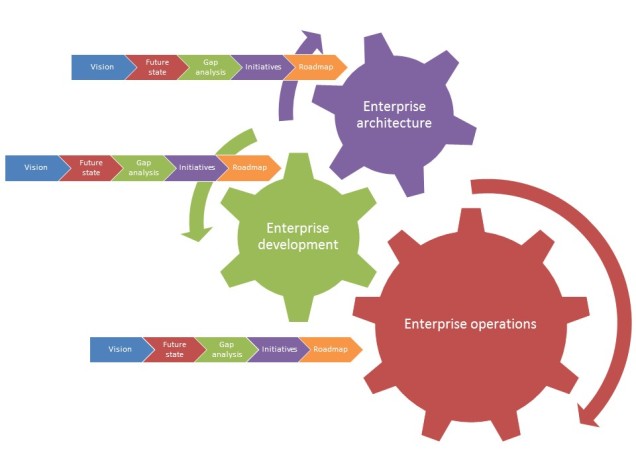

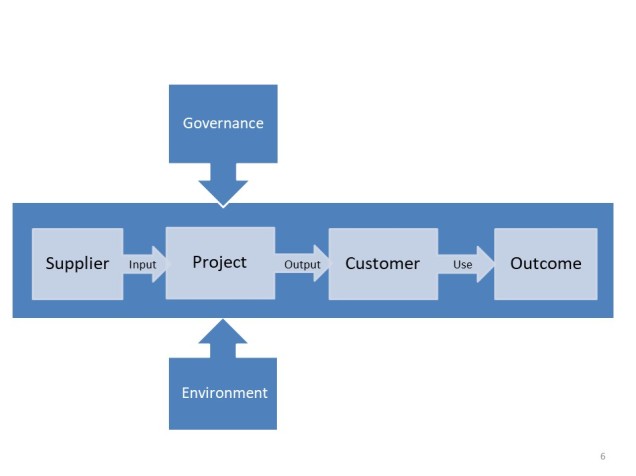

There are, of course, a range of external interfaces that any organisation needs to manage (even a sole-trader organisation). Some of these are shown in the following diagram.

There are also internal interfaces the organisations need to establish and manage, including those shown in the following diagram.

Role

In this role, there are a number of different approaches that have proven helpful, including acting as:

- Babelfish

- Conceptualiser

- Simplifier

- Animator

Babelfish

In this role, picking up the concept from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the babelfish acts as interpreter and translator, helping people understand the different language and terminologies in use, often the different languages and dialects used by different professional backgrounds. The most significant role entails identifying and resolving situations where the same word is being used, but different meanings are intended (but usually not conveyed).

Conceptualiser

Organisations and the ecosystems in which they operate are often quite complicated, making them difficult to understand. In the role of conceptualiser, we develop conceptual models that provide a simpler and clearer representation that is easier to understand. There is also a much lower cost in changing a conceptual model to better reflect shared understanding or to explore future options, whether that be the business model or operating model for an organisation or organisational entity.

Simplifier

The role of simplifier extends beyond developing conceptual models to providing other models or abstractions of the system being considered. This may involve four different modes:

- composition / decomposition

- inclusion / exclusion

- generalisation / specialisation

- ideation / realisation

These different modes are chosen to assist stakeholders to focus on the area requiring greater (or lesser) attention and presenting some challenges in developing shared understanding.

Animator

Last, and certainly not least, is the role in helping stakeholders to distinguish between the animate and inanimate elements of the entity being considered, enabling stakeholders to form views as to where:

- consistency and efficiency is best supported by inanimate systems

- flexibility, creativity and variability is best supported by animate systems (people and teams)

- the interface between the animate and inanimate to establish the most effective outcomes

Value provided

Some of the underlying capabilities that we bring to these roles derive from:

- the wide range of patterns and experiences gleaned across different industries and organisations

- appreciation for the balancing and shifting of the interface (boundary) between social systems and technology systems

- our experience in evaluating relative merits of different positions / options

- the discipline, integrity and assurance that are brought through governance processes

Offer

We offer our service through a variety of different engagement models, based on the preferences, convenience and suitability as determined by our clients. The models and associated service offerings include:

- Learning through webinars, masterclasses, self-paced learning resources

- Coaching and mentoring associated with a variety of executive, management, project and change roles

- On-demand demand services where there is a more significant capability gap or insufficient need to warrant an internal position, offering roles such as on-demand COO, CIO, IT Manager, Program Manager, Project Manager, Business Analyst, Change Manager

- Research activities where clients and Associate jointly contribute to gathering of evidence to better inform evaluation of efficacy of approaches to transformation, change, capability cultivation and leadership mastery.

Over the last two and a half years, I have written and published over 50 articles which relate to architecting and transforming enterprises. These have been published on LinkedIn and an index of all articles maintained in the article “

Over the last two and a half years, I have written and published over 50 articles which relate to architecting and transforming enterprises. These have been published on LinkedIn and an index of all articles maintained in the article “